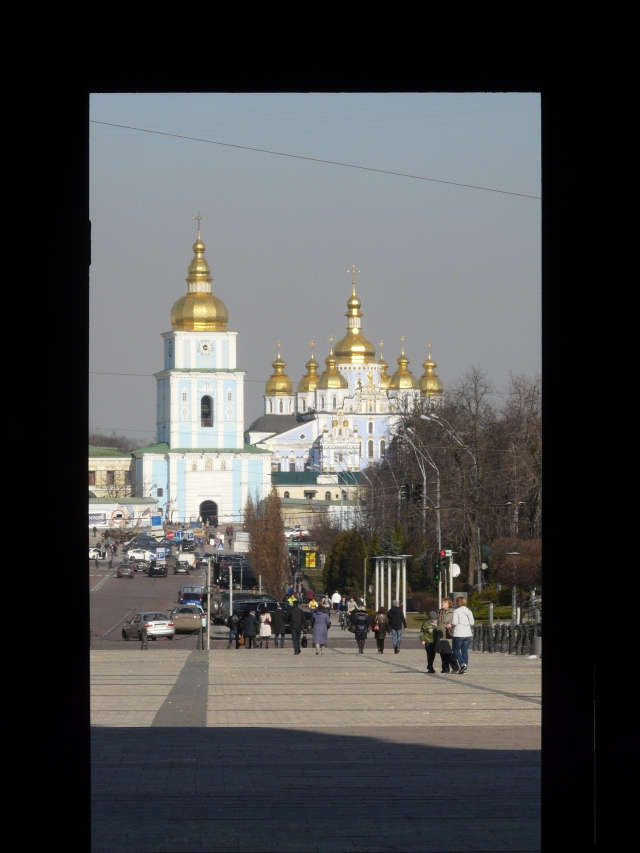

View of St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery in Kiev, where many injured protesters took shelter during the Euromaidan riots and police clashes. (Copyright: Tiago Alexandre Fernandes Mauricio)

Seldom have we read accounts detailing the significance of religion in the Ukrainian crisis. This fact is in stark contrast with analyses reflecting other dimensions of the crisis. The most recurrent ones focus on the role of Russian ethno-linguistics, the power of oligarchs in Ukrainian politics, the consequences for US-Russian relations, and the conduct of asymmetric warfare. Unlike previous crises, events in Ukraine have even been explained through the prism of philosophy as many struggle to understand Putin’s motives.

Most of the reports on religion came from Russia. Moscow was prompt to denounce alleged Ukrainian violence against the Jewish community in Crimea, as “little green men” raided, besieged, occupied, and patrolled key military and civilian installations in the peninsula. This was largely part of a broader misinformation campaign aimed at undermining the legitimacy and power of the new government in Kiev. The campaign was based on accusations that elements from the Right Sector (Pravy Sektor), Banderas, and neo-nazis were conducting reprisals against pro-Yanukovich and pro-Russian supporters in Crimea and in some eastern provinces.

This story, as well as the larger role of religion in the crisis deserves further enquiry.

In a flight from Kiev to Moscow I had the pleasure to sit beside a Catholic vicar from a Moscow parish (whose order will remain unnamed). His accounts shed light in this much neglected aspect of the political turmoil in the country. There are two main points I would like to emphasise. First, the said vicar referred to an ecumenical consensus that is seeking to unite the Orthodox patriarchates of Moscow and Kiev, supposedly to promote a pan-slavic dialogue less conditioned by the diktats from the Kremlin.

Second, since the beginning of the Euromaidan movement there have been efforts to foster an inter-religious consensus in support of the many faiths in Ukraine and thus promote religious dialogue and tolerance. Extremism and violence is to be averted at all costs.

If true, this struggle to bridge the religious divide that is often summoned as supporting evidence in the fight between Kiev and Moscow is welcomed. Considering the religiosity and fervor of the Ukrainian people, this ecumenical undercurrent must not be sidestepped by the political process.